Flags are at half-mast in Montreal following the death of Jean Beliveau, who epitomized both elegance and excellence for the large majority of his 83 years among us, and I’m all out of heroes.

Jacques Demers was asked to come up with one word that described Mr. Beliveau on Daybreak, CBC’s local morning show. He said “integrity,” and will get no argument from me on his choice of words.

My earliest hockey memories are of watching Beliveau captain the Canadiens on the Montreal Forum ice described by Rene Lecavalier in black and white on La Soiree du Hockey. He cemented my allegiance with his performances on the way to the Habs’ 1965 Stanley Cup triumph, the first I remember watching, and one that saw him named the inaugural recipient of the Conn Smythe Trophy.

In the years since I have come to learn a lot more about Mr. Beliveau, both as a player, leader of men and human being. Contrary to the usual effect of time, distance and the media on sports figures’ reputations, the intervening years have only reinforced my decidedly positive opinion.

Penalized players leave the penalty box as soon as the team with a man advantage scores a goal and have since shortly after the game that saw Beliveau pot three in a 44-second span on a single power play.

When John Ferguson took over the single season record for sin bin time with 156 minutes in 1964-65 he dethroned Beliveau who had put up 143 in 1955-56. “Le Gros Bill” took home the Art Ross and Hart Trophies and had his named added to the Stanley Cup for the first of seventeen times in the spring of 1956.

He insisted that a night given in his honor be the starting point for a charitable foundation that was seeded with the $155,000 raised and distributed over two million dollars to helping youngsters before it was absorbed into the Montreal Canadiens Children’s Foundation a number of years ago.

If you wrote him a letter, you’d get an answer, not just a hastily scribbled note and photo with a dubious signature from somebody in the Canadiens publicity department, and if you invited him to attend a minor sports banquet, odds were he’d accept.

If you were a teammate facing difficulties of some sort, unhappy with your ice time, displeased with the coach or less than thrilled with the down side of playing pro hockey, an invitation to tag along with Beliveau for an unannounced visit to Montreal Children’s Hospital after practice often made your problems far less pertinent than they had seemed beforehand.

Beliveau did, very occasionally, disappoint someone. Two Canadian Prime Ministers come to mind. One wanted to put him in the Senate the other in the Governor General’s chair but both offers were politely declined.

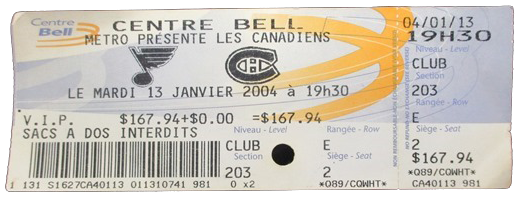

I met Jean Beliveau for the only time on January 13th, 2004, when Rejean Houle was kind enough to allow me admission to the lounge reserved for former players attending games at The Bell Centre.

Much has been written and said about the regal aura that surrounds Mr. Beliveau – that how no matter where he goes, whether it is a hockey gathering or not, a hush falls over any room he enters.

The same hold true when the folks in the room are a bunch of guys who played, traveled and showered with him. There was a palpable pause in all the conversations when he came through the door of Le Salon des Anciens as everyone, consciously or not, acknowledged his arrival.

I spoke briefly with him at one point in the evening but did not ask for an autograph. I did ask for his phone number though, which he was kind enough to write on the back of one of my cards.

Since then I have dialed the number when preparing stories on Bruce Cline and Herb Carnegie and was pleased that he found time to chat briefly on both occasions about his Quebec City teammates from a half-century earlier.

“If they say anything about me when I’m gone,” Beliveau said in his autobiography, My Life In Hockey. “Let them say that I was a team man. To me, there is no higher compliment.”

They’ll be saying that and a lot more.