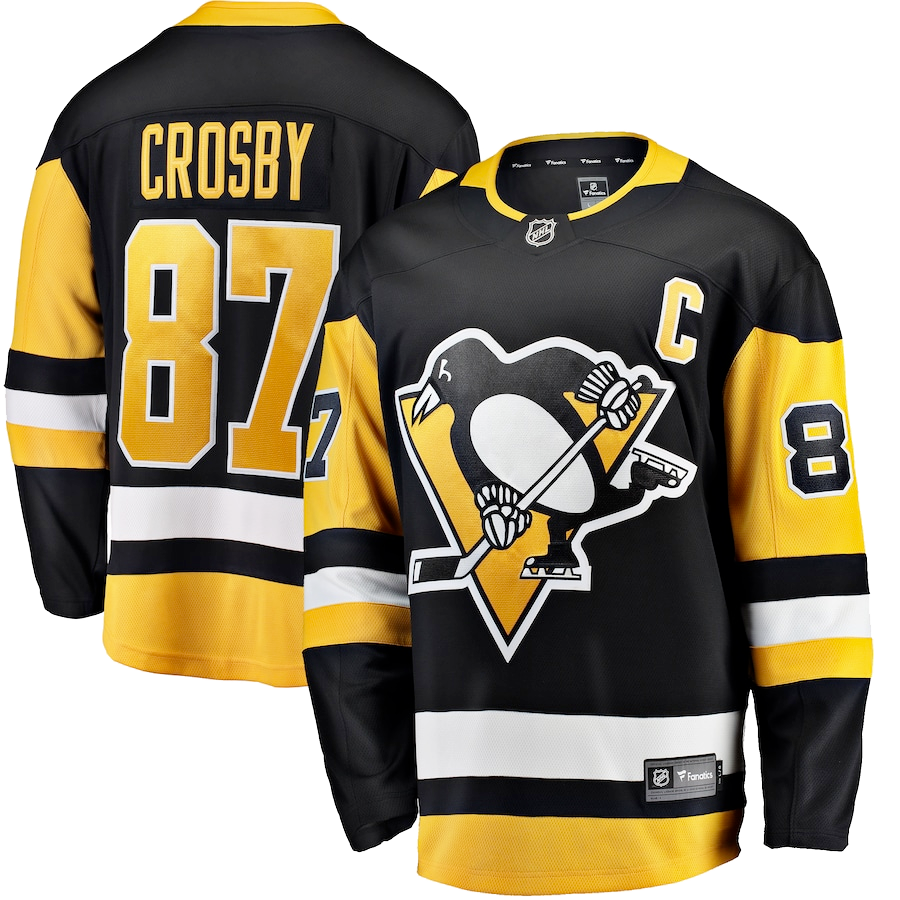

International tournaments have presented some of the most exciting moments in hockey history. From the “Miracle on Ice” in the Lake Placid Olympics of 1980 to the Canada Cup in 1987 and 1991 to the US’s scintillating World Cup win in 1996 to Sidney Crosby’s heroics in 2010, international hockey offers the opportunity to see the best players shine on the brightest stage.

International tournaments have presented some of the most exciting moments in hockey history. From the “Miracle on Ice” in the Lake Placid Olympics of 1980 to the Canada Cup in 1987 and 1991 to the US’s scintillating World Cup win in 1996 to Sidney Crosby’s heroics in 2010, international hockey offers the opportunity to see the best players shine on the brightest stage.

Next month, the world’s greatest athletes will gather in Pyeongchang for the Winter Olympics, but with one notable and very disappointing exception: ice hockey. The National Hockey League (NHL) and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) were unable to come to terms on an agreement for participation, and so the best players will be unavailable.

Instead of featuring Sidney Crosby and Connor McDavid – and perhaps paving the way for the emergence of a new dynamic duo a la Wayne Gretzky and Mario Lemieux – Team Canada’s roster will look as follows in Pyeongchang next month:

In virtually every case, the players to featured on what should ostensibly be a gold medal contender are most notable for what they haven’t accomplished. The roster is littered with players who failed to live up to their pre-draft billing, and it’s reasonable to expect that the quality of play will be more commensurate with a minor league hockey game than with the star-studded tournament to which we’ve been accustomed since the NHL began participating in the 1998 Olympics in Nagano.

It didn’t have to be this way. But where many hockey pundits are still pining for NHL players’ participation, I believe that the real opportunity to improve Olympic hockey lies elsewhere.

It didn’t have to be this way. But where many hockey pundits are still pining for NHL players’ participation, I believe that the real opportunity to improve Olympic hockey lies elsewhere.

It’s important to remember that hockey does things very differently than basketball, football or baseball with regard to player development. In football and basketball, the players arrive “ready for action.” In hockey, like baseball, the NHL drafts players who are just out of high school and (mostly) not ready for NHL action. But unlike MLB, those players don’t get funneled into a player development system that’s run by the MLB team.

During their most critical developmental years, hockey players scatter, some to Canadian junior hockey and some continue playing for their European club team and some play NCAA hockey, but virtually all of them spend their first two years post-draft under the development control of a hockey club that has no connection to the NHL that holds the player’s rights. There’s no minor league system where the parent club can keep a watchful eye on prospects during their most vulnerable and critical developmental time (ages 18-20), actively influencing the player’s development. Instead, the team drafts the player and hopes the developmental process goes well. And the fans – after enjoying some short-term post-draft excitement – sometimes have to wait a half-decade (or longer) for the drafted player(s) to begin making an impact at the NHL level.

Now for the Olympics. Dating back to 1998, the NHL has shut down every four years for the Olympics. It’s a spectacle televised internationally, and it’s ostensibly done to give the NHL great exposure. Except it doesn’t actually give the NHL any exposure. It gives the NHL’s players exposure: the players are already stars, and rarely become bigger stars because of the Olympics.

Now for the Olympics. Dating back to 1998, the NHL has shut down every four years for the Olympics. It’s a spectacle televised internationally, and it’s ostensibly done to give the NHL great exposure. Except it doesn’t actually give the NHL any exposure. It gives the NHL’s players exposure: the players are already stars, and rarely become bigger stars because of the Olympics.

This year, we’re going to watch sub-elite hockey players representing their countries, virtually none good enough to even play in the NHL (much less star). Some of those teams are going to be better coached than others, and there will be some fantastic Cinderella stories to emerge with the big stars on the sidelines (“Three weeks ago, this guy was collecting trash in Windsor!”). But the quality of the hockey won’t be great, and the moment in the limelight will be fleeting for the substandard players who participate.

Imagine instead if the IIHF and IOC worked together so that every four years, the World Junior Championships was instead the Olympics. It would mean moving the WJCs by six weeks, not an insurmountable task. The NHL and NBC could work together to produce team-branded vignettes featuring the players, exposing them to an international audience and getting a head start on branding the next generation of NHL superstars.

The quality of play would be far better than what we’re going to get in the Olympics. In reality the quality of play in the WJCs is actually even better than anything you get with NHL players at the Olympics, because the teams have more time to develop chemistry (they’re not working with an NHL-mandated short break).

Doing it this way also wouldn’t mean exposing those won-over fans to substandard post-Olympic NHL hockey, because the quality of play in the NHL would remain stable. Historically, after the Olympics some players are incredibly tired, most are rusty, and the quality of play is typically pretty bad for a couple of weeks (it’s not unlike the preseason, redux). Locker room tensions can be heightened because teammates have to go from collaborator to competitor to collaborator in a single season. And the injury risk for the players on good teams – who played until late May or June last year, participated in an August Olympic training camp, started preseason in September, used a 2-week “break” to play intense Olympic hockey, then come back to immediately resume the regular season, then play until late May or June again – would be massively reduced.

Turning the Olympics into an investment and celebration of hockey’s future would represent a huge win for the hockey world. It would be far less disruptive to the big-business NHL. It would offer a sustainable opportunity to present Olympic viewers with a truly worthwhile hockey tournament. Watch the highlights (embedded video below) of Canada’s scintillating gold medal win over Sweden in the 2018 WJCs. Watch next month’s Olympic hockey. Which one is better suited for the world stage?