January 2, 2013

By J.P. Hoornstra, AllPuck.com

I’m worried for Jeremy Roenick.

This was not the reaction Roenick intended for readers of J.R., his new book, co-authored with Kevin Allen of USA Today. He said as much on page 4: “Mostly, I hope it makes you wonder, ‘What the fuck1 was Roenick thinking?’ ”

OK, that thought occurred to me too. Roenick is an impressive cocktail of jock vices: Deion Sanders’ joyful love for the spotlight, Dennis Rodman’s2 edgy and flamboyant gamesmanship, Sean Avery’s frat-boy sense of humor3, Michael Jordan’s tenuous relationship with gambling, Dick Butkus’ old-school bloodlust. Mercifully, Roenick also seems to have the moral compass of a Boy Scout. It wobbles from page to page.

But by itself, his persona doesn’t worry me. In fact, I wish the guy were on TV more often. It would make for good entertainment.

No, what worries me is this (page 182):

Anyone who wants to know what life as an NHL player is like should simply review my medical records. I’ve received 600 stitches in my face, broken all of my fingers, had my shoulder rebuilt, suffered two knee injuries, broken my jaw once in four places and another time in 21 places. Then there is the matter of 13 documented concussions and probably 10 to 20 others that were not diagnosed.

In my memoir, the next paragraph would be this:

The clock is ticking. My brain, in non-medical terms, is gradually morphing into a mushy bowl of oatmeal. I’ve seen what Derek Boogaard’s brain looked like at the time of his death, and he only played 419 professional games. I played 1,366. What will my future look like? If my children have children of their own, will I be alive to see them? If so, will I be capable of communicating with them, of knowing them? The clock is ticking, but I don’t know how much time is left.

But this isn’t my memoir, and Roenick doesn’t acknowledge his murky future. His recollection of the post-concussion symptoms is somber enough.

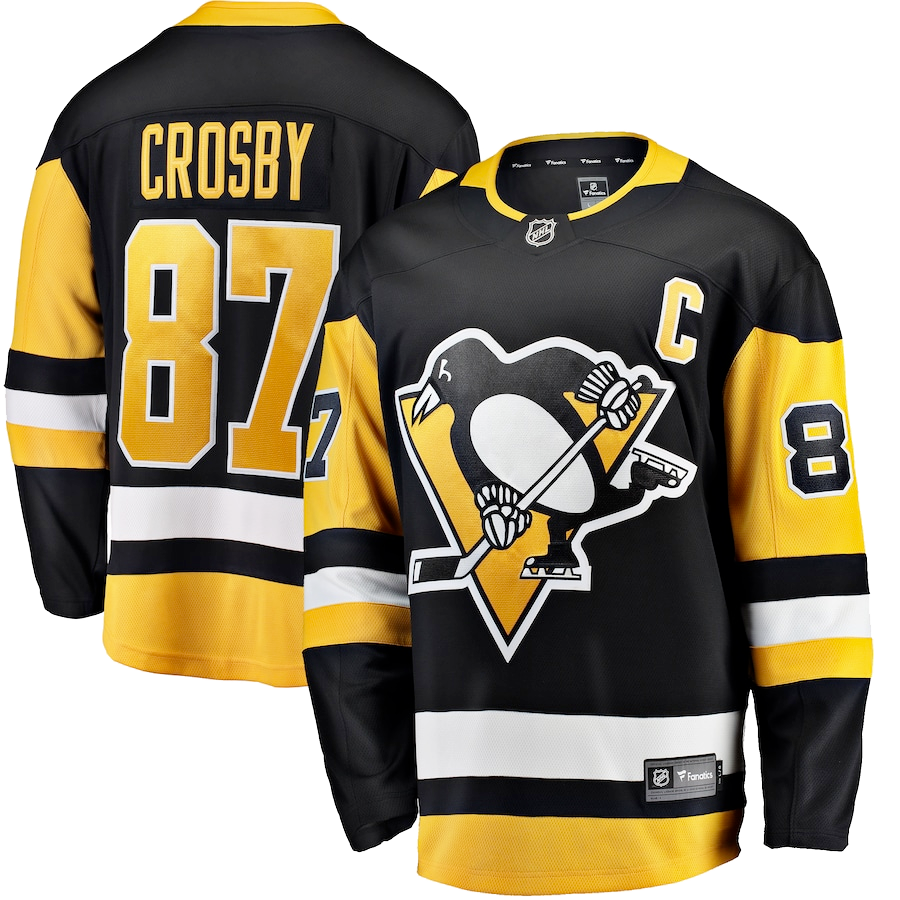

His worst concussion, which he suffered in February 2004, did not lift until January 2005. (Since there was no 2004-05 season, Roenick’s darkest hour remained hidden.) “There was a day during the summer of 2004 when I slept roughly 23 hours,” he writes. If you want to know how Marc Savard and Sidney Crosby spent much of the last two years, ask Roenick.

One key difference is that Savard and Crosby are not outspoken. Roenick is. Already he’s proved capable of flying off the hook on live TV, but what of his future on camera? It’s in jeopardy if Roenick is ever diagnosed with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, the disease discovered in the brains of Bob Probert, Reggie Fleming, Rick Martin, Boogaard and 33 deceased NFL players. Symptoms include confusion, impeded speech and poor judgment.

Roenick’s live-in-the moment attitude is possibly his greatest weakness, but it may be his greatest asset if life is gradually reduced to a depressing fog. I’m worried, but JR might not be.

The rest of the book is a fun, light read. Some good anecdotes. It’s more than a peek behind the curtain but less than a tell-all – very live-in-the-moment.

1. Sports Illustrated counted 158 instances of the “f-word” in the book. It’s the last that will appear in this piece.

2. Roenick writes that he used to hang out with Rodman and Jordan in Chicago during the Bulls’ heyday in the 1990s. Why did I get the feeling that he left out the best stories?

3. Roenick’s verdict on Avery: Good guy.